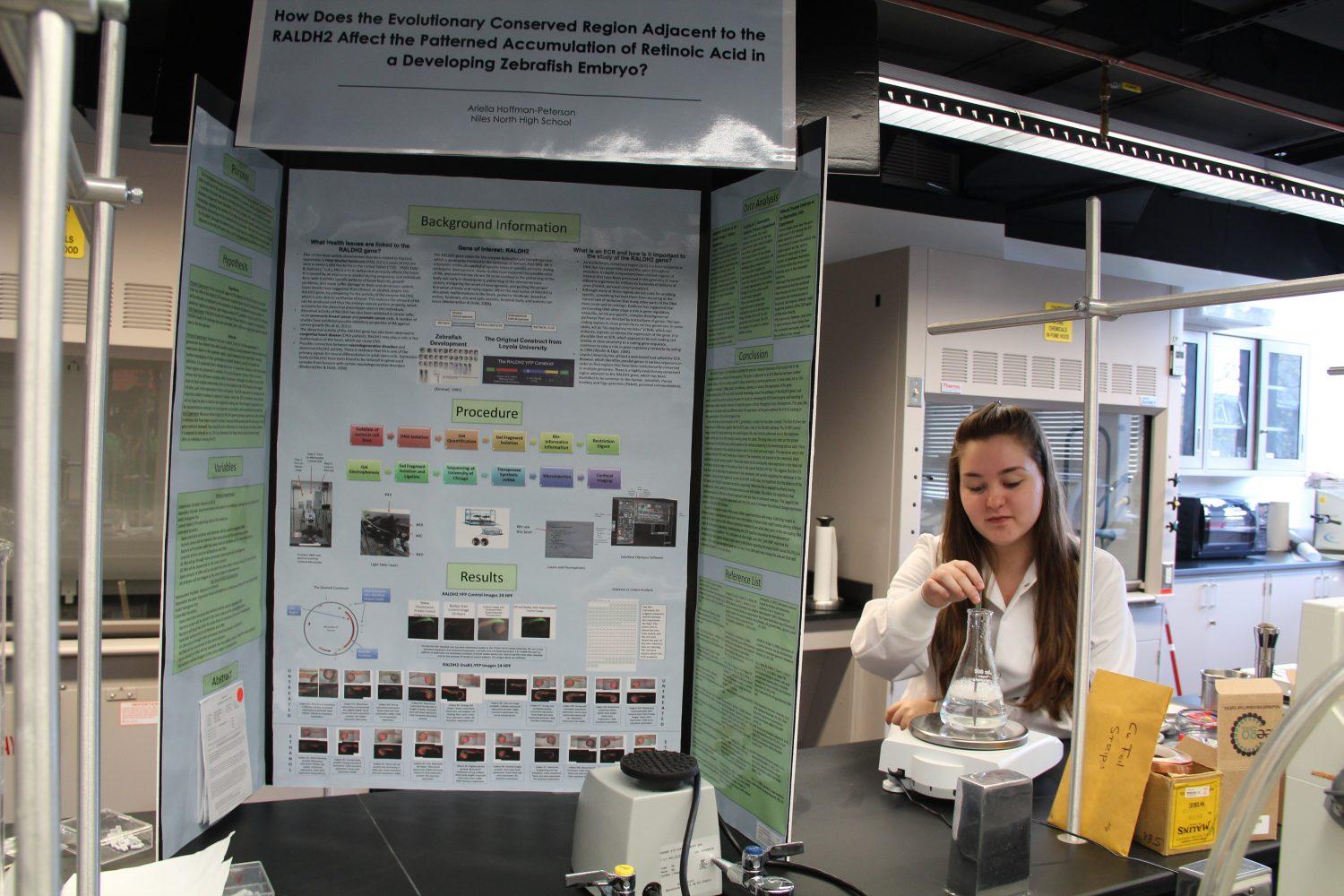

As is the case with nearly every student in the Science Inquiry and Research (SIR) class, science is a major passion for Ariella Hoffman-Peterson. However, unlike many other students, Hoffman-Peterson’s passion has extended far outside the lab at Niles North. Her Sophomore year she began an internship conducting Food Allergy Research at Children’s Memorial Hospital. Before her junior year she received the REAP scholarship apprenticeship at Loyola University, beginning research on the RALDH2 gene that would lead her to the honor of participating in the 2011-2012 Intel Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) as a senior.

In this year’s project, Hoffman-Peterson tackled the “evolutionary conserved region adjacent to the RALDH2 gene” to track how it “affected the patterned accumulation of retinoic acid in a developing zebrafish embryo.” At first glance, Ariella Hoffman-Peterson’s project may seem dauntingly complex. After numerous explanations and even diagrams, it still is. However, even to an ignorant observer, it’s obvious that Hoffman-Peterson’s project is not only uniquely exploratory, but highly relevant and important research.

The project’s central focus concerns a gene known as RALDH2; this gene plays a vital role in the patterning of an embryo, or making sure various body parts develop correctly and in the correct locations. The RALDH2 gene is responsible for levels of Retinoic Acid which directly helps pattern an embryo during development. It has implications for diseases ranging from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders. Adjacent to the RALDH2 gene in an organism’s genome is an evolutionary conserved region, or ECR. Although this region does not code for a specific protein, it is considered conserved because comparing many species shows it has not mutated at the natural rate that most non-coding DNA mutates at. An ECR can potentially act as a switch for a gene such as the RALDH2, though its function is not fully understood. When alcohol is introduced into an embryo’s environment, however, the ethanol competes for the gene’s activity, resulting in the physical defects associated with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. By removing ECR from the gene construct and alternately inserting plasmids with or without the ECR into zebrafish embryos, and with the help of some yellow fluorescence, Hoffman-Peterson was able to track the effects of this region on the development of the embyro.

Since many organisms have the same gene which similarly affects their development, Hoffman-Peterson decided to work with Zebrafish, as their transparency and quick generational time allowed her to easily track gene’s role in the development of the zebrafish. Ultimately, she noticed a strong trend: the fish with the ECR intact saw heavy expression primarily in myomeres (giving rise to highly important muscles lining the spine) and not in many other regions. Fish without the ECR had almost no myomere expression, but saw expression in the notocord, which develops the central nervous system. This lack of myomere expression would be extremely problematic for the developing embryo, as myomere expression is an essential part of development. Hoffman-Peterson also took the project a step further, attempting to directly analyze the effect of alcohol on the process, but has relatively inconclusive evidence on the subject at the time.

As Hoffman-Peterson prepares to present her project at ISEF in Pittsburg this May, she already has a lot to celebrate. At the local science fair level alone, she has received five awards, including being a finalist for the IJAS State Science Fair in the paper and project sessions, a U.S. Army Award for Outstanding Project, best in her category and a finalist at ISEF. She looks forward to learning from her peers and exploring all the amazing research fellow high school students will be bringing to the international fair.