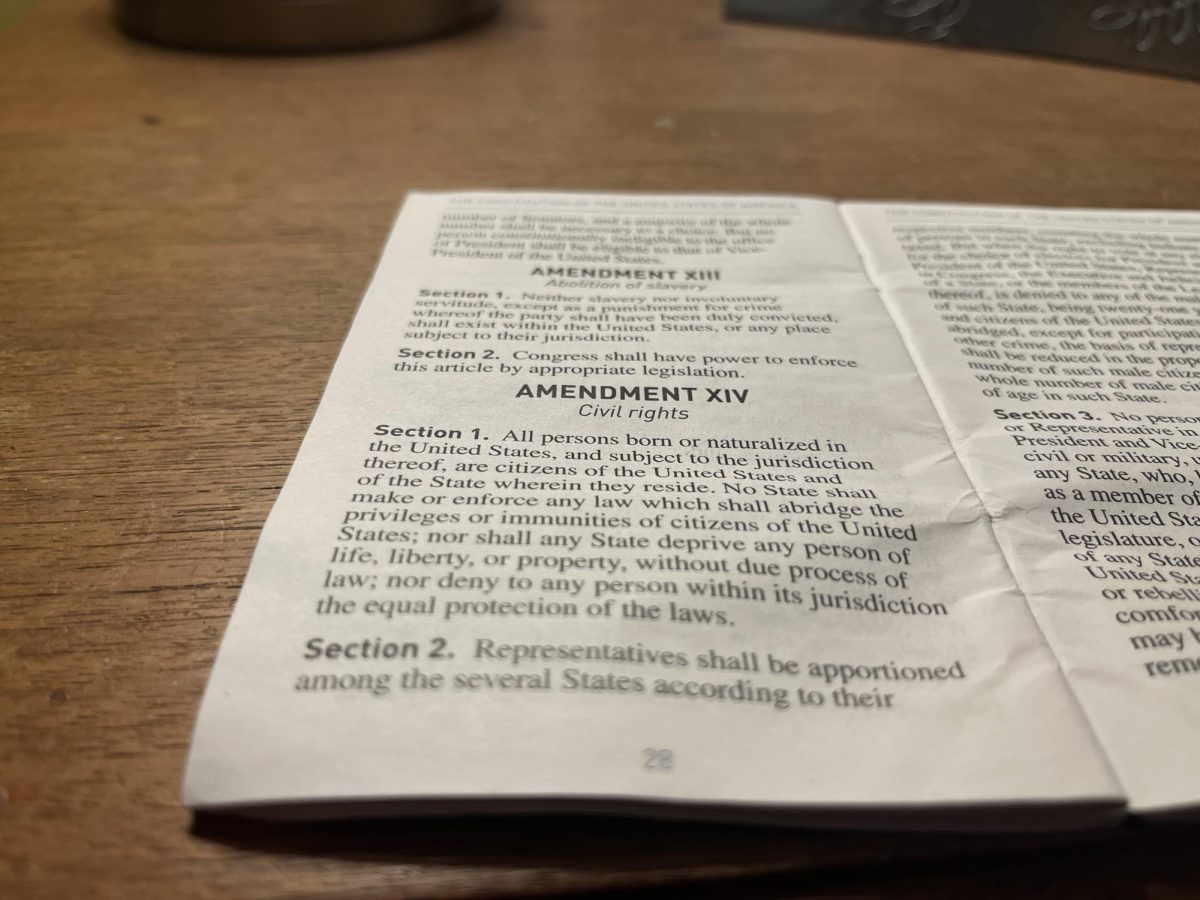

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

So begins the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, added to the United States’ highest governing document in 1868. Now, 157 years later, a fight has emerged in federal court to determine the true meaning of that single sentence.

The Fourteenth Amendment guarantees “birthright citizenship,” the ability of any person who is born on U.S. soil to be considered a citizen of this country, regardless of whether their parents had been born there or not. President Trump contradicted that policy, though, with a Jan. 20 executive order. It commanded federal organizations not to affirm the citizenship of anyone born in the United States after Feb. 19, to a father who does not reside legally and a mother who either does not reside legally in the US, or does for only a limited period of time. U.S. District Judge Deborah Boardman of Maryland struck down the order across the country with a preliminary injunction on Feb. 5, in a case brought by immigrants’ rights groups CASA and the Asylum Seekers Advocacy Project, alongside a group of five pregnant immigrant women. The following day, U.S. District Judge John Coughenor of Seattle issued his own nation-spanning preliminary injunction against the order, after having previously enjoined it until a hearing on Feb. 6, in a case brought by four states, including Illinois. A total of 22 states sued the Trump administration on Jan. 21 to prevent the order from taking effect, alongside Washington, D.C. and San Francisco. The American Civil Liberties Union, joined by other advocacy groups, has also sued.

The Trump administration argues that the children delineated in the order are “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, as per the Fourteenth Amendment—therefore, they do not have an automatic claim to citizenship. Meanwhile, other coverage of this issue has pointed to a Supreme Court case which would contradict this reasoning: in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, the court ruled that the son of two non-citizen Chinese immigrants to the U.S. was himself a citizen. Forbes reports that most of those with expertise in the law would disagree with the administration.

Should the executive order fail, some congressional Republicans have proposed laws which would alter designations of US citizenship. On Jan. 23, Rep. Brian Babin of Texas proposed the “Birthright Citizenship Act of 2025,” which would provide for birthright citizenship to only be granted to those with one parent, at the minimum, who legally resides in the U.S., or who serves in the country’s military.

Kristy Pommerenke-Schneider, an AP Government and Politics teacher, was uncertain how a law like the one Babin proposed would hold up. “That goes against the Fourteenth Amendment,” Pommerenke-Schneider said. “I think that those laws would be challenged right away, as they should be, and I think people will sue.” Pommerenke-Schneider, like Judge Coughenour in his injunction, said the Trump administration would need to seek a Constitutional amendment in order to put an end to birthright citizenship — a laborious process, Pommerenke-Schneider noted.

Trump’s order only applies to those born after Feb. 19, but even for some Niles North students with citizenship, it’s cause for concern.

“I do agree people should come here legally, but the process is so long that by the time people get approved to come here, something tragic could happen in their home country that could result in their death,” senior Elyana Kachaochana said. (ImmigrationHelp advises that it can take one and a half to two years to gain full U.S. citizenship.) Kachaochana can speak of the wait time with experience, having immigrated to the U.S. from Syria with her family at about age four.

“I feel like this isn’t the only thing that they’re trying to accomplish,” Kachaochana said of the executive order. “I feel like they’re going to expand upon this.”

Junior and Latinx Club member Gabriel Marin-Luna expressed concern as to the possibility of the order being ultimately weighed by the Supreme Court.

“You have a Supreme Court that is six-three conservative, and you have a justice system that for four years, Trump, during 2016, 2020, was able to fill with people loyal to him,” Marin-Luna said. “So, hypothetically, a case could go through all the conservative channels, to the Supreme Court, that then finds a wacky way to interpret the 14th Amendment that basically invalidates [birthright citizenship].”

“I want to remain optimistic and hopeful that there are judges that will, especially on the Supreme Court, that will rule…to keep birthright citizenship,” Pommerenke-Schneider said. “But I don’t know.”

Any students needing assistance related to immigration can turn to this list of resources, shared with teachers.