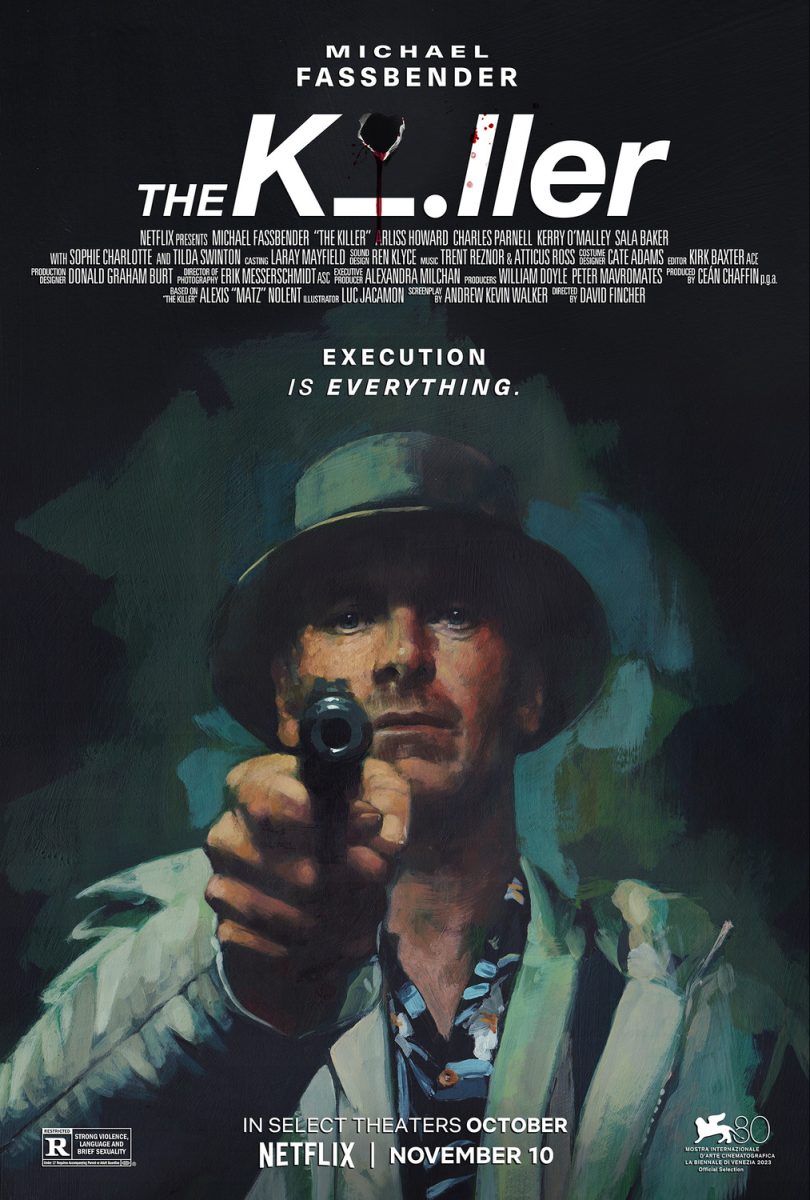

What stands out most about The Killer is its simplicity. In a time where formulaic big-budget Superhero films dominate cinema, an extreme on the other side of the spectrum has intensified. Over the past few years, renowned auteur filmmakers have almost solely put their talents into long and maximalist period-piece dramas, for better and worse. Nolan’s thrilling Oppenheimer and Scorsese’s exhausting Killers of the Flower Moon stand out in recent memory, alongside many, many more. David Fincher’s response? A 1 hour and 58-minute meat and potatoes action-thriller, and in that, he delivers.

The Killer revolves around an assassin (Michael Fassbender) who is always in control and an unexpected chain of events that test that. The film opens with the unnamed contract killer peering out of a hotel room in Paris, scoping out his next hit. We are met by his narration, the philosophical and oftentimes comedic thread that ties together the story. He explains to the audience, but also himself, that he does not believe in luck, karma, or justice. He’s just doing his job. It’s all a routine to him. He eats a McMuffin with blood on his hands. He listens to The Smiths on his iPod with a sniper prodding his shoulder. He glances at the FitBit on his wrist, whatever it takes to get his heart rate low and his mind focused, like a surgeon before a procedure or a businessman before a big sales pitch. He incessantly reminds himself to stick to the plan, to only fight the fight he’s being paid for, and that he must “forbid empathy” because it makes him weak and vulnerable. His murmurings of nihilism sometimes teetered on eye-roll worthy, feeling a bit too edgy and trite, but more often than not they landed well enough.

Immediately, I was reminded of the nihilism found in some of Fincher’s earlier and lesser works like Fight Club. However, Fincher’s handling of this theme nearly 25 years later is drastically different. Rather than the sophomoric, loud, and (falsely) attractive nihilism of Fight Club, The Killer is much more toned-down, cold, and matured. It is the fiery hot angst of Fight Club frozen over into something much more distant and bleak. It is a testament to David Fincher’s metamorphosis as a filmmaker, from his abrasive and rough-edged films of the 90s to his subtle and finely-cut films of the mid-2000s and beyond.

Anyway, nihilism is the pill that the hitman takes to deal with his line and of work, to muffle any sort of moral reckoning for his career’s killings (which he describes as a 1.000 batting average). It has worked like a charm. But when he misfires his sniper by a split second and hits a bystander, allowing his target to slip away, his peaceful living as a cold-blooded killer is disrupted. An international manhunt ensues while simultaneously, the killer seeks revenge of his own from those who’ve wronged him. Each step of the way, his life as well as his attitudes of personal nihilism and professional perfectionism are threatened by a myriad of people and events.

It is a thoroughly engaging and exciting thriller storyline, but sometimes its story beats feel a bit less sharp than they could be, leaving the film feeling kind of wandering in structural limbo. Regardless, the director-writer duo of David Fincher and Andrew Kevin Walker, who last brought us the renowned Seven in 1995, know when to throw you a bone to reel you back in when your mind starts to wander. That tripled with stunning visuals and an intriguing Michael Fassbender makes The Killer hard to look away from.

The killer’s name is never revealed, but it hardly matters. Fincher makes a point out of including every one of the dozen or so different fake names airport clerks, bank tellers, and post office workers call him by. It’s like the scene in Fight Club where Ed Norton’s character, suffering from a lack of purpose, talks about how everywhere he travels, he uses single-serving everything; packets of sugar and creamer, travel-sized bottles of shampoo and mouthwash. For the killer, his identity is single-serving: interchangeable and disposable. Unlike Norton in Fight Club, however, he is content with it. Why? We never really get an idea. We find out his law school teacher in New Orleans, with a side hustle of contracting hitmen, convinced the killer to “stop studying law and start skirting it,” as he puts it, but the full picture of his backstory is never delved into. We find out he has a girlfriend in the Dominican Republic, but how they met and how long they’ve known each other is never revealed. There’s a cold feel to The Killer. It is a peer into a lifeless life.

The Killer keeps you at an arm’s length. By the end of the whole ordeal, the hitman recluses into his Santo Domingo home alongside his girlfriend. There’s a noticeable shift in his demeanor. Perhaps he’s receded from his life as an apathetic assassin and softened up a bit. But there is no gaudy emotional catharsis or tragic event to signify it. There will be no Oscars handed out for The Killer, and Fincher has no interest in such. That’s refreshing.