African American Vernacular English isn’t broken, the education system is

Photo accredited to The State News

African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is its own language with its own set of grammatical rules.

“You know Legend teachers gon’ hear him speak and think he stupid right?”

“But you know he not. He smarter than we both was at his age,” I emphasized.

“We know he smart cause we his family, but dem White folk finna hear him talk and know he from da ghetto. They not gon’ listen to a word he gotta say long as he talk like dat.”

I was with my family on the South Side of Chicago where I sat and got my hair braided; I spent hours folded in between the legs of my older cousin, Amber, as I multitasked, holding back groans of pain and responding to her heavy concerns regarding her son’s first day of kindergarten. Amber was proud to admit that she got him into “one a’ dem good schools,” as opposed to the underfunded and predominantly Black school in which he was previously enrolled. I was happy to hear that Legend would be getting a better opportunity to learn overall, but I couldn’t help to acknowledge the fact that one of the first things he would experience at school would be an attack on his language and, interchangeably, an attack on his intelligence.

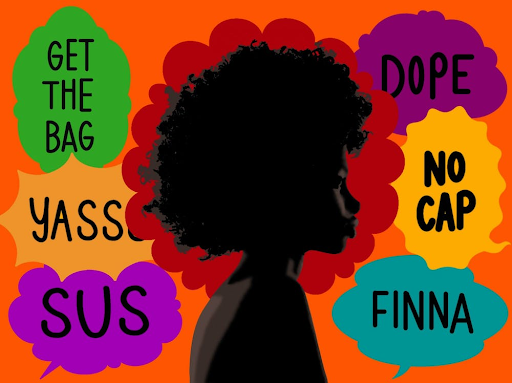

Legend and a majority of my family are users of African American Vernacular English (AAVE). AAVE is a vocabulary that has been created by African American communities going back many years. AAVE is systemic and rooted in history, acting as an identity marker and expressive resource for its native speakers.

We have a long history of assuming that whatever Black people do is defective. There is a widespread belief that those who use AAVE are uneducated or unintelligent, and this can have problematic repercussions for how many Black people live. People harbor negative assumptions about the different ways people speak, having profound effects in areas such as education, renting an apartment, getting job interviews and even interactions with the police. All these different things are made difficult for Black people just based on an accent or dialect.

The systematic grammar patterns of AAVE have been scientifically studied and verified over the past 50 years, combating the stigma that AAVE is “broken” or “incorrect” English. AAVE is a valid form of speech; it is a full-fledged dialect of English that is entirely rule-bound. In some contexts, the words “is” and “are” can be left out. There is a habitual aspect marker and a remote present perfect marker. There are double negatives and the preterite had. AAVE has grammar rules and if you do not follow these rules, it results in ungrammatical sentences and side-eyes from native speakers.

Black students are often forced to code-switch. Currently, around 80 percent of teachers in public schools are White and from middle-class backgrounds. These demographics are relevant because most of these teachers can’t relate to or understand the language of Black children. Therefore, I implore that any teacher who is among Black English-speaking students needs to take the time to learn the basic linguistic structure of AAVE. There are books and articles to be read that educate on the language. In the classroom, teachers should empower students for being speakers of two dialects. Standard English, though chosen to be the official dialect, it is by no means linguistically superior.

Niles North English teacher Barbara Hoff shared her experiences with AAVE in the classroom. “I actually went to a workshop a couple of years ago and there, there were a bunch of professors, some of the leading scholars, that talked about it’s [AAVE] use in the classroom,” she said.“That was really my first big confrontation or exposure to this, especially in the way people talk about it now since I feel like it’s changed over time in education and how we look at it.”

She continued, “They really opened my eyes to thinking about Black language as having set rules of grammar and coming from the historical reality of slavery, and the possible reasons as to why that version of language is always subordinate to Mainstream Academic English. It made me think about how I talk about AAVE in the classroom and how to make different versions of English more acceptable.”

I asked Ms. Hoff her how she felt about writers using AAVE in their pieces of work and she said, “I’m fine with it because it’s not a mistake, it’s not slang, and it’s following common rules. It isn’t the English that I grew up speaking but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t as good as the English I grew up speaking…Some teachers can be conflicted about that, but how much should we be requiring students to codeswitch to be successful.”

For some time following that conversation with my cousin, I began to notice that I’ve been forced to code-switch around non-Black preference at the expense of my expression to avoid targeting by the police of academic professionalism. I’ve received praise for my degree of articulation and syntactical skill, but whenever I strayed away from Mainstream American English on my assignments I’d receive back a paper marked with red circles and, ultimately, a lower grade, despite the accuracy of my work.

So I learned to conform, conducting myself in a manner deemed respectable to Whites to the detriment of my Blackness. I feared that AAVE would make me a target; AAVE was gang-affiliated, saggy pants , and criminal. I worked to conceal my identity, fearful of giving off signs that I was an intruder in their version of America.

However, as I continued to navigate their world, I realized that no matter how respectable I was, I was always going to be a Black girl. Truth is, my language is rooted in the African Holocaust and the fight to survive amidst European hegemony and colonial influence. It is not ghetto nor ignorant; AAVE is my theory of reality and the core of who I am, the only language adequate to serve the needs of a Black child functioning within a Black society.

Through storytelling, we can reimagine ourselves. We can create fictional characters that challenge contemporary circumstances or retell the stories of those who lived before us. Through storytelling, history is conveyed and lessons are taught. As we free ourselves through writing, we get a better grasp on our own identities and sense of well-being.

The art of storytelling is why language is so important. Storytelling mobilizes African spirits to performatively speak a new reality into existence—the salience of the oral tradition in Black storytelling stems from the ability to name and breathe life into new worlds. African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is a story within itself, a creative force that has contributed to our cultural life and linguistic innovation. As a society, we need to rid ourselves of our antagonism toward AAVE and instead celebrate it.

Journalism has given me the opportunity to join the conversation and bring my Black voice— what I’ve learned and hope to further explore as a Black woman— to academic spaces. My language allows me to flip the script; I can put Blackness on the forefront, sharing my authentic self with the world. So, lemme holla at you for a minute! My linguistic expression is where grandma fries catfish, where brothas run game, where sistas talk that talk, where the streets keep it real; it’s who I be.

Jasmine Nichols is a Senior at Niles North who aims to write about contemporary issues within the black community. She enjoys learning about black history,...

Nicole • Nov 19, 2024 at 11:32 am

I think this is very good!!

Cynthia Fey • Apr 20, 2023 at 1:25 pm

Thank you, Jasmine, for another powerful piece of journalism! Stephen Pinker’s 1994 book The Language Instinct introduced me to the idea that AAVE has greater linguistic precision than conventional English. “He be working” is the phrase that I remember as having greater depths of meaning than the less exact “He is working.” Keep up the great thinking and writing — thanks for sharing!